Navigating through fragmentation

CREDIT: ISTOCK (RAPIDEYE)

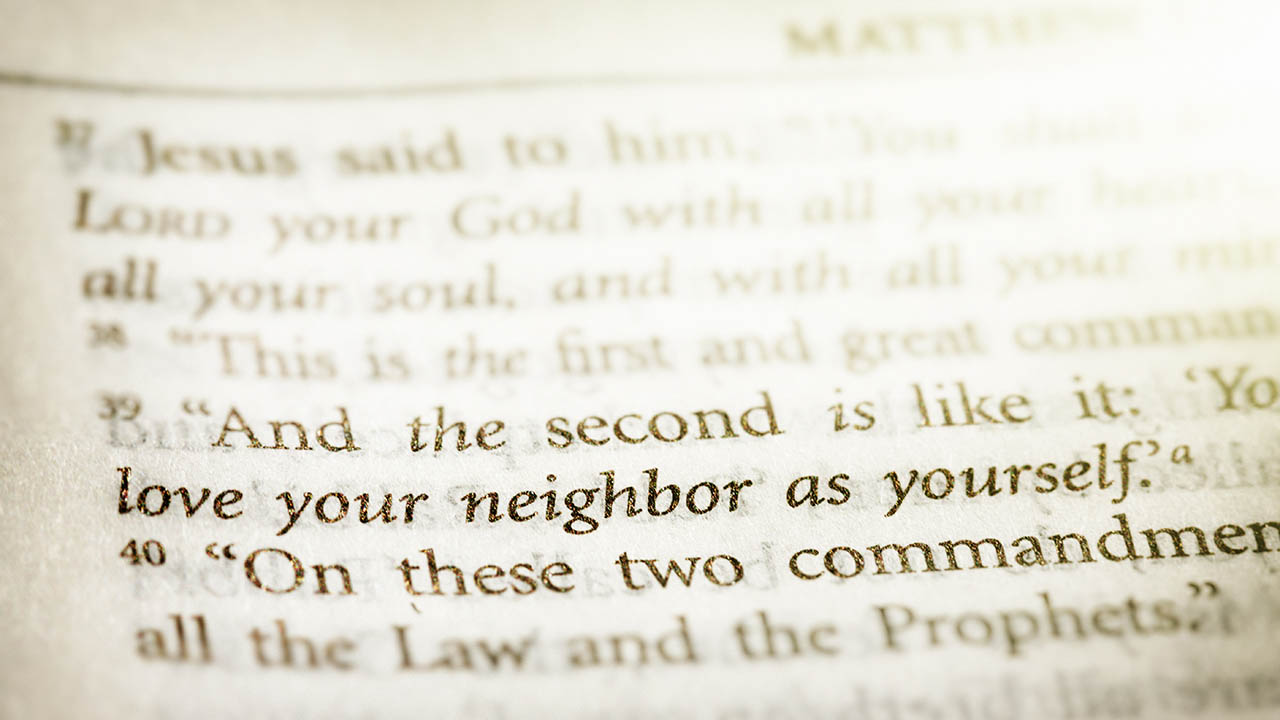

CREDIT: ISTOCK (RAPIDEYE)Opinion: Our modern experience of community is the most fragmented in history, but the New Testament's teaching of "Love thy neighbour" still rings true.

Before, say, the year 1900, most people did not travel much. Newspapers were common I think, but telephone and telegraph communications were expensive and not often used by consumers.

Chances were that if your ancestors were European, the Canadian town in which you died was the town in which you were born. You personally knew the farmer who produced the vegetables you ate and the carpenter who built your house.

The odds were good that if you had had a disagreement with someone during the week, you and they would be in the same church service on Sunday morning, quite likely hearing the priest, minister, or pastor speak about some aspect of Jesus’ command to love your neighbours, even the disagreeable ones. Most of your family members lived nearby, and the graves of those who had died were not more than several hundred metres from where you lived.

I am not trying to suggest that life was idyllic. Alongside the white culture that dominated Canada at the beginning of the 20th Century was the oppressive reality of life for Indigenous people. Diseases still took the lives of many children. Domestic abuse, crime, boredom, hard physical work, and mental illness were all part of the scene (as they are today).

But very likely people had a stronger sense of community, rootedness and belonging. You lived your entire life alongside the same people. Everyone you saw probably knew your name. You likely knew many of the hardships and the joys, the sins and the virtues, of nearly all the people you encountered each week.

Not so today. The low cost of travel and communication means that increasingly we are fragmented.

There are bits and pieces of us lying all over the planet. We go to school with one cluster of people. Our vacations are spent with another.

Family members we grew up with may be living on one of the country’s coasts or in one of Asia’s shoreline mega cities. We play online games with one community and share posts with a different social media community. People in my circles have done work terms in the Canadian Arctic, Texas, the Middle East, and any number of urban centres around the world.

As if the complexity of our lives is not challenging enough, the future can also look terrifying. The effects of climate destruction seem to be bearing down on us. The increased use of surveillance technologies and data mining threaten our sense of personal freedom. And although gender-based discrimination has been addressed to a large extent, there is always the fear that it may increase.

How can one keep their head when there are so many trends that fragment our experience of community, that cut away at our rootedness in any one place, and that undermine our confidence in the future?

The writers of the Jewish holy writings (the Christian Old Testament) lived in troubled times. Their people experienced war, exile and massacre. Even in better times, all was not well.

Often their own leaders exploited them. Although they did not possess our modern technologies and habits, they knew dislocation, disorientation, and a fragmentation of their sense of wholeness.

Yet, those writers offered a path through such fragmentation. It was the pursuit of righteousness. We often think of “righteousness” in the sense of an arrogant imposition of one group’s standards on another.

Not so those Jewish writers. For them, righteousness meant adherence to the laws of God. The laws of God were considered “the way”, “the truth”, and “life”.

To change one’s attitudes, words and actions in accordance with those laws was to bring wholeness. It brought integrity that allowed an individual or a group to withstand the whirlwind around them. It gave the community guidance for living, even during times of persecution and exile.

The laws of God, for those writers, were not unknown. They were possessed in written form and would have been committed to memory. Some are less relevant now than when they were unveiled (and some only barely relevant today). I wrote about the Top Ten just a few weeks ago. But they boil down to two: Love your neighbour as your own self; and above all, trust God.

Love your neighbour. That is, speak truthfully, work for what you need, don’t damage another person’s marriage, be honest in business, and so forth.

And, trust God. Trust God, because, in the end, wholeness and integrity aren’t grounded even in your and my commitment to live a righteous life. We might not be all that good at it anyway, especially in our earlier years.

In the end, integrity and wholeness that can help us get through times of fragmentation are grounded in one thing: the presence of God. The presence of God, and letting his laws shape our habits and plans through all of life.

Editorial opinions or comments expressed in this online edition of Interrobang newspaper reflect the views of the writer and are not those of the Interrobang or the Fanshawe Student Union. The Interrobang is published weekly by the Fanshawe Student Union at 1001 Fanshawe College Blvd., P.O. Box 7005, London, Ontario, N5Y 5R6 and distributed through the Fanshawe College community. Letters to the editor are welcome. All letters are subject to editing and should be emailed. All letters must be accompanied by contact information. Letters can also be submitted online by clicking here.