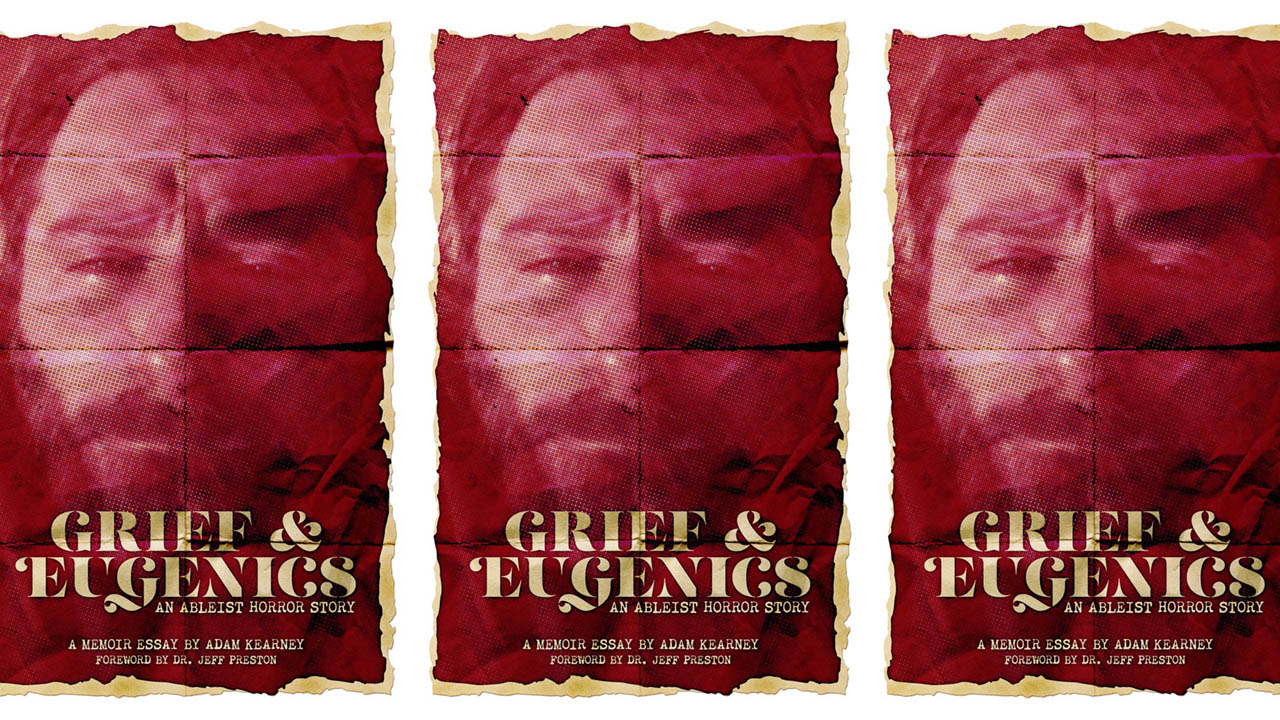

Grief & Eugenics: An Ableist Horror Story, Part Two

CREDIT: COURTESY OF ADAM D. KEARNEY

CREDIT: COURTESY OF ADAM D. KEARNEYThe depiction of disability in religious texts has lasting impacts on the way society views people with disabilities today.

This article is Part Two in a series of excerpts from Fanshawe grad Adam D. Kearney’s essay, Grief & Eugenics: An Ableist Horror Story.

Growing up I struggled a lot with not being “normal” and unable to participate in the same activities as my peers. Sure, finding a participation ribbon on my desk after track and field day was a nice attempt to make me feel part of the class. In reality it was a lesson in the half measures society would rather be seen trying to make an attempt at rather than instead of making the effort to truly be inclusive. After all, while my classmates ran, jumped and shot put their way through the day, I was at home playing River City Ransom on Nintendo. If anything, the ribbon acted as a lasting reminder of how I was actually excluded from the event. However, I was taught that I should be thankful for what little I was given and not rock the boat by asking for too much. Why is it seemingly so hard for society to be more inclusive for folks with disability? Disability isn’t anything new, so why is there still such a struggle for awareness, understanding and acceptance? This often looks like accessing systems that were designed and built to purposely exclude people with disability. I can personally speak to the lasting effects of social segregation, othering and bullying as it slowly builds and reinforces tremendous amounts of self-loathing, which is sometimes referred to as Internalized Ableism in the disabled community. This is the feeling that we are less than, not of value, and not worthy of what non-disabled folks take for granted.

This inherent privilege non-disabled folks enjoy is challenged when they are forced into addressing disability. This is because disability is something they think they have not witnessed in their daily life. This is largely because of generations of isolation and institutionalization of people with disability. When the situation does arise and non-disabled folks come faceto- face with disability it comes as a bit of a shock. I say shock, specifically, because if you saw the looks I get when I wheel through a Walmart, there isn’t a better word to summarize the expressions I observe when we make eye contact. At its core, I believe what they are actually experiencing is the realization that their privilege of good health is potentially fragile and indeed temporary. That at some point in their life, unless they die first, they will become disabled, either acquired from an injury or just simply from the aging process, and rather than accept this truth they push it away like a toddler with a plate of Brussels sprouts. As though it is a choice. As though they can protect themselves from it. Sometimes people’s gut reactions say more than words ever can. This fear is nothing new though–it has been documented for millennia.

Years ago I picked up a book called The Origin of Satan by Elaine Pagels at a bookshop strictly because I thought it sounded metal and badass. Like a lot of books I have purchased, it sat on my shelf for a while. Honestly, it was well over a decade after I picked it up that I read it because I had found a memoir written by an Italian exorcist in the Catholic church (An Exorcist Tells His Story by Fr. Gabriele Amorth). I thought it would be interesting to start with the origins of the devil before moving onto how one evicts them from a meat suit. It turned out to be enlightening to read them from my perspective as both disabled and person in recovery.

The term Satan is derived from the Hebrew verb “to obstruct, oppose,” and it is not until later on in the Bible that we are introduced to the actual personification that we recognize today. It wasn’t the Devil that tempted Eve but a talking serpent. The real embodiment of Satan doesn’t happen until the back half of the bible (the New Testament), corresponding with a time when the Christians were at war with the Roman and Jewish peoples. This is why even to this day the character of Satan embodies a lot of anti-Semitic stereotypes; he was the personification of evil, and was used as a tool of persecution. Early Catholic scripture would continue to demonize and vilify the things that they feared and didn’t understand.

The Bible is filled with stories of Jesus’ miraculous laying of hands and praying over people, casting out demons, absolving sins and forgiving transgressions. People with paralysis could walk again, blind/deaf regained senses, lepers were cured and reunited with family and community. What lasting narrative do these stories create being passed down over generations and millennia? I have had more than a handful of awkward situations where people tell me that they will pray for me to “get better.” I feel like it isn’t a huge jump that in the minds of many, disability is inherently evil or wrong and must be cured at all cost.

I remember at a rather young age watching TV one Sunday and coming across Peter Popoff. If you are unfamiliar with his antics in the 80s, he was a televangelist, clairvoyant and faith-healer. He was the guy you likely remember laying a hand on a wheelchair user’s forehead, praying over them, and then having them jump up and start dancing after being absolved of their sins and having the demon cast out of them. To say I was shocked would be an understatement. The potential of being cured of OI, of no longer breaking bones, needing endless surgeries, and being able to participate in track and field. Finally, I could try to win something better than a participation ribbon. As the TV show continued, it turned out that I didn’t even have to go down south to find Prophet Popoff. I could send away for a small vial of miracle water for a nominal fee, of course, that would cast the demons out of me.

Obviously, I immediately asked my mom for the money to buy the holy water. She shot me down. I then asked if we could go see him so I could be cured of my evil affliction. That is when my mom had to explain to me how he was a fraud and was lying to people to get money from them. When I asked about all the people dancing in the aisles who were once in wheelchairs like me, she told me they were actors. This rather quick interaction shattered a lot of illusions in my little mind surrounding faith, religion and an individual’s personal intent.

To be continued…

This memoir essay was published as a zine in Jan. 2023. If you enjoy it and feel you would like to support the author, you can find a pay what you can PDF or purchase a physical copy at handcutcompany.com.

Editorial opinions or comments expressed in this online edition of Interrobang newspaper reflect the views of the writer and are not those of the Interrobang or the Fanshawe Student Union. The Interrobang is published weekly by the Fanshawe Student Union at 1001 Fanshawe College Blvd., P.O. Box 7005, London, Ontario, N5Y 5R6 and distributed through the Fanshawe College community. Letters to the editor are welcome. All letters are subject to editing and should be emailed. All letters must be accompanied by contact information. Letters can also be submitted online by clicking here.