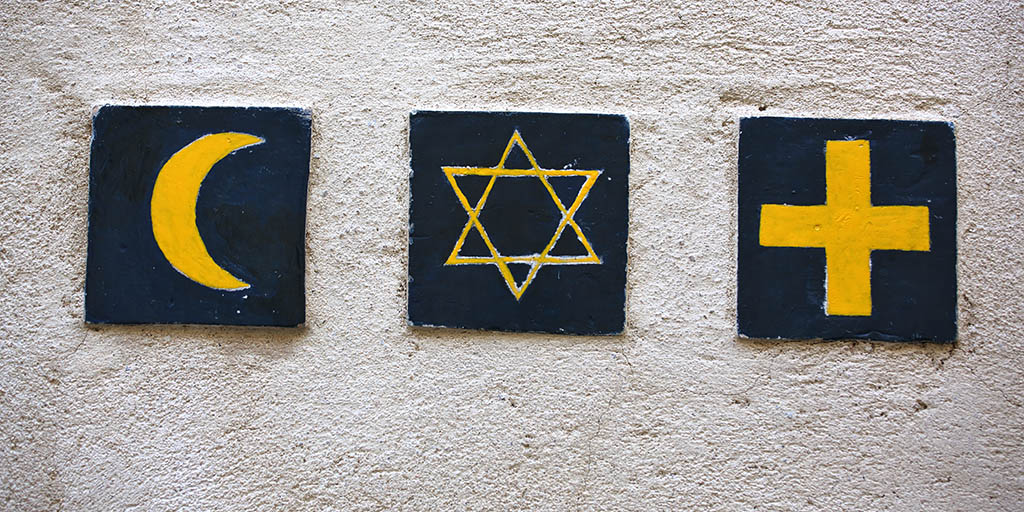

Inconvenient religious symbols

CREDIT: ISTOCK (ZANSKAR)

CREDIT: ISTOCK (ZANSKAR)Should public servants be banned from wearing religious symbols?

By now you have probably heard that Quebec has a new law that bans public servants in positions of authority from wearing religious symbols. The most obvious domain in which this is making a difference is the world of public education. This week there are reports about teachers being turned away from jobs because they insist on wearing their religious items of clothing.

“Remove your hijab or find another career.” The same message applies to wearers of the Jewish kippa, the Sufi turban, and other faith symbols. Consequently, some are choosing not to teach, and Quebec school boards are struggling to find enough educators.

Then there is the Catholic crucifix, a representation of Christ’s death. Ironically, there is a large one hanging in the Quebec legislature. It may become a target.

I have not discovered any complaints about the wearing of smaller crucifixes or crosses. However, they are obviously religious. It stands to reason that they will be banned as the law becomes more widely applied. That is because, according to the law,

“A religious symbol, within the meaning of this section, is any object, including clothing, a symbol, jewellery, an adornment, an accessory or headwear that is worn in connection with a religious conviction or belief; or is reasonably considered as referring to a religious affiliation.” (Bill 21 of the Coalition Avenir Quebec government.)

The rationale for preventing religious symbols from being worn by public servants in positions of authority is that the Quebec government is secular. That means that its representatives and employees must stay clear of giving the impression that it favours one religion or other.

But why should religious persons be so adamant about showing their faith by means of what they wear? This may come a surprise to uninformed secularists, but any religion worth its salt claims that it is of the greatest importance for everyone, not just for its current adherents. Indeed, if it did not make such a claim it would have no adherents. The wearing of a religious symbol is an invitation to others to consider that religion.

Preventing the free stating of one’s faith by means of wearing symbols of that faith, then, has the effect of offending the person of that faith because it implies that the person is deluded in thinking that anyone else should be, or would want to be, interested in that faith. That person does not agree that wearing such a symbol is a matter of mere individual preference. That person believes, in fact, that the world cannot be explained at all without reference to that faith.

What can be made of what is happening in Quebec then?

During the ’60s, Quebec leaders created a cultural shift. The Catholic Church was quietly but forcefully ejected from its position of authority. The shift is known, actually, as The Quiet Revolution. Quebec chose a path of political secularism.

Today, because of immigration, other religions have appeared in Quebec. Many of its adherents have no interest in keeping their faith to themselves or ceasing to reveal it when they are working as public servants. Consequently, the success of secularism appears threatened. This time the threat does not come from the Catholic Church. It comes from the faiths introduced largely by immigrants to Quebec.

Added to this unease about the possible erosion of the progress of secularism is the discomfort over certain expressions of the new (to Quebecers) faiths. These include Sharia law and the wearing of clothing that hides the face or the entire body. All the more reason to strengthen the secularization of the province.

It seems to me that another approach is needed. Requiring someone to stop wearing symbols that are deeply important to them is not wise. It creates resentment. It could motivate religious people to form their own institutions. Specifically, it could spark the creation of more Muslim, Christian, Jewish, Sikh, and other schools.

I’m not saying at all that the creation of such schools would be necessarily bad. But what I would say that an increase in the number of such schools would undermine the program of secularization which Quebec’s leaders apparently cherish.

My own understanding is that we should expect to live in a world where religious symbols are found everywhere. Religions are not about to disappear anytime soon. They appear to be increasing. A casual drive through Toronto, for example, reveals the proliferation of new churches from the global south and east. Mexican workers near where I live have their own van to get them to work and back. On it in big letters: Jesus Saves. God is always going to attract at least as much interest as, say, the Conservative or Liberal Parties of Quebec.

The wearing of religious symbols should be left up the wearer. It may be challenging for a Muslim father to notice that his daughter is being taught by a teacher wearing a cross pendant. It may be require a serious discussion between a Christian mother and her son to deal with the fact that his math teacher wears a hijab. A secularist might not particularly appreciate that his son has a high school soccer coach who wears a turban and likes to talk about his faith. The world is full of inconveniences. Many of them are opportunities.

There is a Jewish law that says we must love our neighbour as our own selves. Jesus, in rebooting Judaism, stated that it was one of the two greatest of the laws of God. It seems to me that allowing the neighbour to wear items that are important to him or her is simply to treat them as they want to be treated. That’s the starting point. The rest we can sort out.

Editorial opinions or comments expressed in this online edition of Interrobang newspaper reflect the views of the writer and are not those of the Interrobang or the Fanshawe Student Union. The Interrobang is published weekly by the Fanshawe Student Union at 1001 Fanshawe College Blvd., P.O. Box 7005, London, Ontario, N5Y 5R6 and distributed through the Fanshawe College community. Letters to the editor are welcome. All letters are subject to editing and should be emailed. All letters must be accompanied by contact information. Letters can also be submitted online by clicking here.