Jordan Peterson's read on the Bible's "Coming-of-Age" story (and how to improve on it)

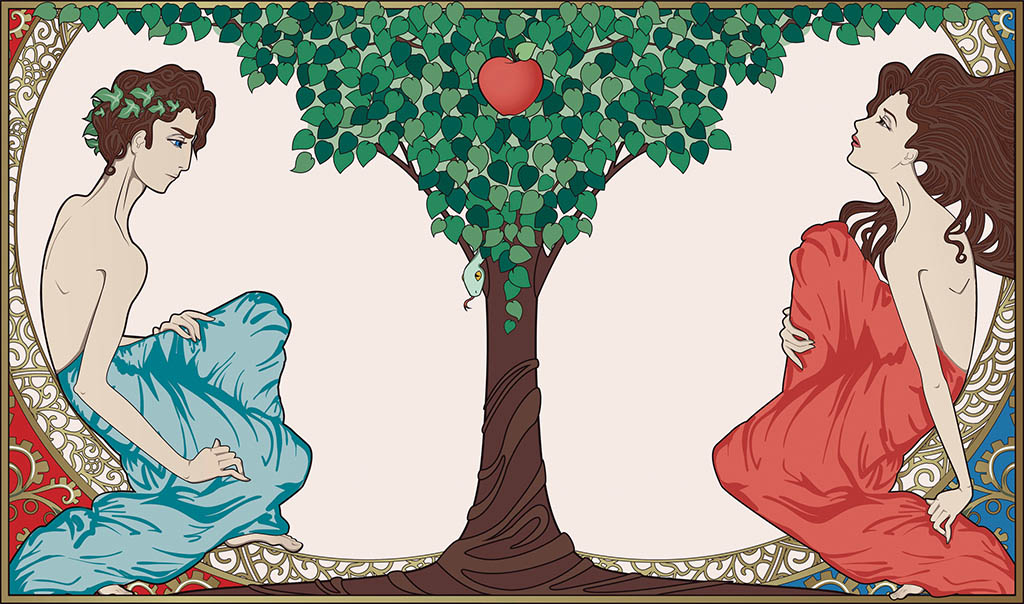

CREDIT: DRAKONOVA

CREDIT: DRAKONOVAUnderstanding and interpreting stories from the Bible can be a different experience for many, but the idea of awareness and falling from grace is something to consider when reading these stories.

Jordan Peterson is known for offering unexpected perspectives. His views on Marxism, Feminism and Gender are contentious to some. Sachin Maharaj, a PhD candidate at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, wrote in the Toronto Star last February that Peterson challenges those who want to automatically label and dismiss people who hold “unfashionable views.”

A professor of Clinical Psychology at the University of Toronto, Peterson is widely known for emphasizing the importance of responsibility and meaning over rights and happiness.

People are paying attention. Socialblade reports that Peterson currently has about 1.5 million subscribers and 76 million YouTube views. By way of contrast, the same site reports that Drake's numbers are in the many millions. Still, Peterson's following is impressive.

One of his most popular works is the lecture series, The Psychological Significance of the Biblical Stories. You can find it on YouTube. (The first talk alone has been viewed over 3 million times.) Peterson believes that the stories of the Bible are of enormous significance. I agree.

But I think that Peterson's read on the Bible stories can be improved on. I'll refer to his use of just one of those stories and his use of it to make my point.

In his book (he has written only two), 12 Rules for Life — in the chapter titled “Rule 2” — Peterson explores the Bible's story of “The Fall.” The story itself appears in the first “book” of the Bible, Genesis. Genesis means, “beginnings.” You'll find the story just a couple of pages into it.

Here's how the story goes. Many know it. Adam and Eve are living in the Garden of Eden, a Paradise. A clever, we should say cunning and deceptive, creature enters the picture. It offers the couple the opportunity to be like God, “knowing both Good and Evil”. All they need to do is violate the one command God has given them, the command to not eat the fruit of The Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil.

The creature is subtle, suggesting that God knows that Adam and Eve will become like him, or equal to him, if they eat the fruit. It is God's (petty) desire to remain privileged that motivates him to withhold that important knowledge from the pair. Once Eve first, and then Adam, eat, all hell breaks loose. Childbearing and food production grow arduous, even dangerous. The clever animal looses its legs and is sentenced to grovel. The couple is driven out of the garden into the reality of a harsh world. They realize they are naked and desperately seek to cover themselves.

How does Peterson understand this story? For him it is a comingof- age story. It reveals the historical development of a double awareness: awareness of our world and awareness of self. We came to this double awareness through our long evolutionary past.

Peterson argues that we are not fully aware as long as we remain in the garden, to so speak, protected like children from the suffering of life. Nor are we fully aware until we realize, like Adam and Eve, post-Fall, that we are vulnerable- naked. All of life, in order to be meaningful, is a response to the suffering of life and to our individual and communal vulnerability.

So, we can see how, on the basis of this story and the view of life Peterson sees it supporting, he challenges those who focus primarily on rights and the pursuit of happiness. He maintains that above all we must pursue meaning by accepting the responsibility to reduce suffering in the world. If you get happiness, as he famously says, great. But don't chase it.

And, actually, this is what I often tell the people who I work with in my current practice as a chaplain among youth who are convicted of crimes. My prescription, however, is based not on Peterson's view of the story of the Fall.

So here's where I have difficulty with his view that this story is in essence a coming-of-age story: It fails to take into account the view of the story that is embedded in Genesis itself. In the context of Genesis the Fall is colossal disaster. It ushers sin into the world. It is the beginning of our long tragic journey into abuses, discrimination, death camps, and weaponized sex.

The account of the Fall is an anti-coming-of-age story. This is because in the Genesis context our coming of age was already in process. It was well underway. Here's what I mean.

In Genesis, Chapter 1 humans are blessed with the freedom to spread out over the world. A formidable undertaking. In Chapter 2 they are co-orders with God of the world, and co-creators, and co-celebrants. (I've written about this in other columns.) In fact they consult with God. He regularly meets with Adam in the “cool of the evening” to consider their journey together.

This is at the very heart of our coming-of-age; to trust our Creator, and shape to our lives in relationship to his formidable and enriching presence. The story of the Fall reveals that from day one we've blown it.

Why does Peterson take the view of the Fall that he does? This brings us to the influence of pioneering psychoanalyst Carl Jung on Peterson. Maybe I can try to comment on that some other time.

So, I think Peterson's take on The Fall does not fit the context of the story. It therefore needs re-thinking.

Nevertheless, his working with that story and with much of the rest of the Bible is something of great importance. There is no other collection of documents (it is a collection) that has had, and is continuing to have, as powerful a civilizing effect on our world. Peterson, considered by many a leading intellectual, perhaps the leading intellectual of the Western world, is bringing to the attention of many the stories of the Bible. And for that I deeply respect him.

Editorial opinions or comments expressed in this online edition of Interrobang newspaper reflect the views of the writer and are not those of the Interrobang or the Fanshawe Student Union. The Interrobang is published weekly by the Fanshawe Student Union at 1001 Fanshawe College Blvd., P.O. Box 7005, London, Ontario, N5Y 5R6 and distributed through the Fanshawe College community. Letters to the editor are welcome. All letters are subject to editing and should be emailed. All letters must be accompanied by contact information. Letters can also be submitted online by clicking here.