Notes From Day Seven: Civil rights on the other side of the planet, Part 1

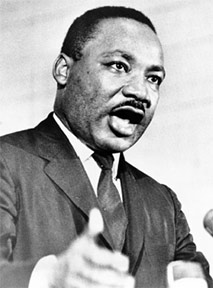

CREDIT: DRMARTINLUTHERKING.NET

CREDIT: DRMARTINLUTHERKING.NETAmerican civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

About two weeks ago it was 50 years since August 28, 1963. That was the day that the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I have a dream” speech in Washington, D.C. Praise for King, a Baptist pastor, and this speech (he gave many other speeches and sermons) poured out via the Internet, radio, and printed media all through that week.

An assassin killed King shortly after the speech. But his work did not fail. The United States saw anti-black laws that harkened back to the days of slavery in the South struck down.

One of the interesting things about that most famous of King's speeches is the backand- forth between King and audience. Watching the video (it runs less than 20 minutes, and YouTube even posts a condensed version of about five minutes) you might feel like you are at a Black church service. As King's passion begins to rise, the audience cheers and applauds like a Black church audience voicing its “amens” in response to a sermon.

But it is not only the audience interaction with King that brings to mind a church service. It is the content of his speech. The speech, especially the closer it gets to the end, is shot through with phrases lifted straight from the Christian Bible. King spoke about Blacks and their White supporters not being satisfied “till justice rolls down like water and righteousness like a mighty stream.” He recognized that some, just released from jail for marching in civil rights protests, had come through great “trials and tribulations.” He spoke about storms of persecution. He spoke about the redemptive power of suffering, a key motif throughout the Bible, especially in the New Testament (Jesus' suffering brought forgiveness for sin and release from death).

King spoke about the Christian creed that God “created all people as equal.” He looked for the day when “every valley [would] be exalted, the rough places made plain, and the crooked places made straight.” Again, expressions straight out of the Bible. As he came to the end of the speech, King spoke of the day when, through the abolition of racist laws, “the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together.”

This hope in the glory of the Lord, King said, was the faith that would carry him back to the South where his work would continue. Then, recalling the story of God releasing the Israelites from slavery in ancient Egypt, King ended with the thrilling words, “Free at last, free at last, thank God almighty we are free at last.”

Civil rights is no longer the issue in the United States that it was half a century ago. Since then, perhaps the most famous — and successful — struggle for civil rights took place in the 1990s. Apartheid was abolished in South Africa. Again, as with the civil rights movement of the 1960s, it is not possible to imagine that that would have happened without the imagination and courage of Christian leaders, especially that of Anglican Bishop Desmond Tutu. And the post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Hearings were founded on the Christian understanding that injustice must be brought to light and reconciliation must be achieved for a nation to move forward.

Today, with many changes taking place on the other side of the world in China, that country is emerging as a source of civil rights advocates, often persecuted. However, perhaps because the Chinese government evicted Christian organizations from China during its “Cultural Revolution,” there is no noticeable Christian underpinning to the civil rights movement there. Next week I will look at the art of Ai Weiwei who is perhaps the most well-known rights advocate in China today. While his art has been on display in the Art Gallery of Ontario all this summer, he is not permitted to leave his country.

With the absence of Christian motifs, his work has a different accent from that of Rev. King. Nevertheless, is there a connection between Ai Weiwei's art and the message of the Christian church? More next week.

Michael Veenema was a chaplain at Fanshawe College until 2004. Currently he lives in Nova Scotia where he is a Presbyterian minister serving a United Church congregation, and is a chaplain with the Department of Justice.

Editorial opinions or comments expressed in this online edition of Interrobang newspaper reflect the views of the writer and are not those of the Interrobang or the Fanshawe Student Union. The Interrobang is published weekly by the Fanshawe Student Union at 1001 Fanshawe College Blvd., P.O. Box 7005, London, Ontario, N5Y 5R6 and distributed through the Fanshawe College community. Letters to the editor are welcome. All letters are subject to editing and should be emailed. All letters must be accompanied by contact information. Letters can also be submitted online by clicking here.