Vampires losing their bite

WINNIPEG (CUP) — Between movies like Twilight and TV shows like The Vampire Diaries, the modern vampire appears more daft than horrific.

It certainly hasn't happened overnight, so maybe it's possible to retrace our steps over the past few decades in attempt to pin-point the period where the bloodsucker became a lovable, endearing character.

In 1966, ABC premiered its new daytime soap opera Dark Shadows to mixed reviews and worse ratings. The show originally followed a young woman named Victoria Winters, hired by the mysterious Collins family to take care of their 10-year-old boy.

Facing possible cancellation, producers began adding new plotlines and characters to the show in attempt to garner some form of interest. After seeing marginal ratings boosts from adding a s�ance and a ghost to the show, producers went for broke in 1967 when they introduced Barnabas Collins, a 105-year-old vampire ancestor released from his chained coffin in the Collins family crypt. Ratings exploded.

Dark Shadows would use the classic vampire image to sell almost every aspect of the show from then on out. For all intents and purposes, Barnabas Collins was the new main character of the series. Indecently, the actual term "vampire" wasn't used to refer to Collins until more than a year after his character was introduced. Dark Shadows effectively had a vampire character without really having a vampire character.

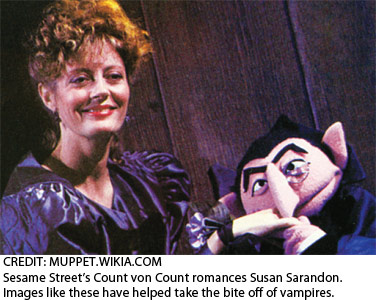

Then in 1971, General Mills introduced their new line of monster- themed breakfast cereals headlined by one Count Chocula. As if the vampire could get any less scary, one year later PBS's Sesame Street introduced the number loving Muppet Count von Count, a distant relative of Count Dracula.

What Dark Shadows, Count Chocula and Count von Count all have in common is that they were all able to achieve success utilizing a cultural symbol that is so well recognized it doesn't really have to be explained.

At this point, the idea of the vampire is such a general concept that it is fairly easy to play around with the nature, the rules and the implications of the character. It is for this reason that you can have a vampire that on one hand teaches children mathematics and a vampire on the other hand that hawks cereal. Certain rules apply only when you need them to.

The trend of more-or-less friendly, sympathetic vampires continued throughout the '70s and '80s with Anne Rice's novel Interview with the Vampire, followed by films like 1987's The Lost Boys and Near Dark. Interestingly, in each of these stories there are both depictions of a gang-like underground vampire culture as well as a tortured main character who learns life as a vampire isn't all it's cracked up to be.

Another interesting change made to the vampire formula during this transformative period was the fact that the vampires became substantially better looking, basically made to look like male and female supermodels. In these cases the vampire began to occupy roles of fantasy, more accurately depicting an ideal than a nightmare.

In an interview with USA Today, Eric Nuzum — author of the tremendously readable The Dead Travel Fast — states that: "(Very) rarely are vampire stories (actually) about vampires. They are often about desire, love, forbidden pleasures, forbidden fears that people are too scared or embarrassed to admit. Put it in the guise of a vampire, and you can talk about it. They are the perfect metaphor for anything that challenges you or makes you lose control."

Under this description, the vampire tends to embody more of an empty symbol and it certainly explains why there is such variation, not only in the nature of the character, but also the rules by which the character must abide.

Consider again both Count Chocula and Stephenie Meyer's Twilight series. How often is it necessary with any of these characters or any of these stories to explain the nature of a vampire? These images are already so well understood that any explanation is redundant. This, in a way, is why breakfast cereals can advertise using bloodsuckers and teen romance novels can enjoy the presence of an undead teen idol — you don't really have to deal with any of the more messy elements.

In his book Religion and Its Monsters, Timothy K. Beal describes monsters as otherness within sameness, and perhaps we can use the same description here.

The vampire as a symbol always carries with it a certain mystique, the allusion of a hidden reality that lies behind the curtain, something forbidden. And yet this forbidden element is always implemented in a different way depending on the cultural context and situation. The vampire exudes an otherness, but it is the sameness that gives it away. Whether the vampire is framed as a teenager, a European aristocrat or even a muppet, there is always more revealed in the sameness than there is in the mysterious otherness. What is familiar about any particular rendition of the vampire reveals needs, curiosities and even fears of the culture from which it emerged.

Perhaps the readers of Stephenie Meyer's books are just as fearfully curious about sexuality as frequent viewers of Sesame Street are fearfully curious about adding and subtraction.