I must be dreaming: How I cope with dissociation

CREDIT: LAM LE

CREDIT: LAM LEOpinion: If you struggle with dissociation, you're not alone.

There’s been a running joke going around social media for years about how if we stand in the mirror for too long, we begin to lose a sense of our being and we get this strange thought that life could be a simulation.

This kind of thing only happens if you stand in the mirror for a really long time, or if you say your name over and over again until it sounds like a made-up word, or if you’re just really stoned. However, for some people, this is just a day-to-day occurrence.

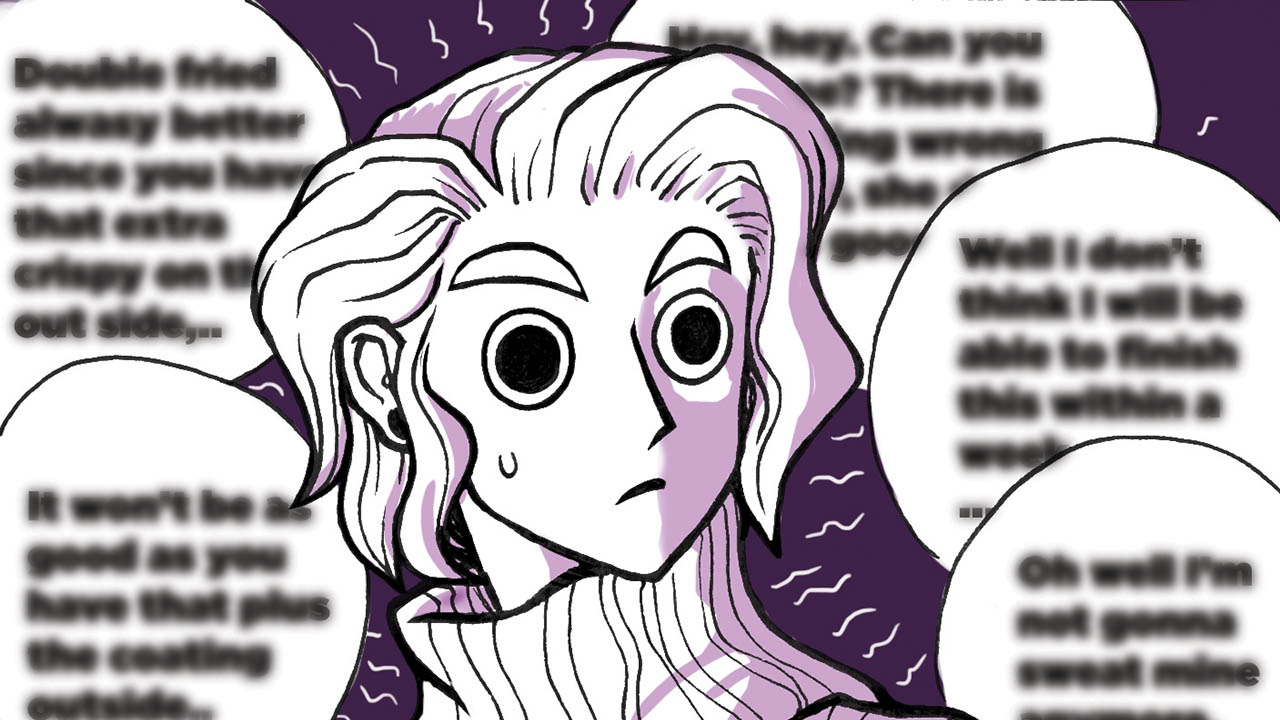

It’s called dissociation. It feels like astral projecting, or being absolutely baked, but not in the fun way. However you want to describe it, it’s not a safe nor comfortable feeling. It feels like you’re floating, like your feet could leave the ground at any second or simply just fall through.

Imagine. You look in the mirror and you see yourself, you’re looking into your eyes but at the same time, you’re just looking straight through. You can touch your face and feel your skin, but is it really yours? Are you just dreaming about seeing yourself in a mirror right now? When will you ever wake up?

I’ve explained to so many people in so many different ways what it feels like to dissociate. No one fully understands besides my mother and my grandmother, who also started experiencing it in their late teens just like myself. I try not to explain it too in-depth to anyone else for the sake of not sounding insane.

If you’ve never experienced dissociation, you must know how it feels like you’re living in a dream. Your surroundings seem somewhat fake or two-dimensional, like you’re watching your life play out through a screen. Not trying to sound dark, but nothing feels real.

To understand why it happens is understanding that the brain is its own, well, brain. It has a mind of its own, literally and figuratively. Sometimes if the brain finds itself in a situation it doesn’t like, it’ll clock out for a few hours. Maybe days. Maybe months. It takes off and leaves you on auto-pilot as a coping mechanism that is completely out of your control.

It may sound like a brilliant concept for some people. The idea of not being fully present during an emotional or traumatic moment in your life sounds convenient and helpful, but it is really just a dreadful feeling of disconnect.

When I dissociate, I feel emotionless and numb. It weighs me down when I feel nothing in my chest, ironically enough. When I first began experiencing dissociation, I would tend to veer away from social gatherings because I’m scared I’ll look or sound crazy.

Dissociation makes me so paranoid about the way I look and how I talk. It’s hard to focus and engage in conversation. It’s hard to say anything other than “yeah” and “no”. It really goes hand in hand with stress and anxiety, and together they create an unholy cycle.

I was terrified to be going back to school after taking a year off. I had never dissociated while attending school, so naturally I was quite nervous about what the future held for me in college.

It hasn’t been as hard as I thought it would be. It is still frightening at times, and some days are more difficult than others, but I have managed to take care of myself fairly well. My dissociation doesn’t require me to have extra assistance in my classes, but it can be very difficult to focus and study. Some days I get to class and wonder how I got there. Another big part is questioning if I’m even really present.

Dissociation is the largest obstacle I deal with in my life. It makes me worry that it will ruin my relationships, my well-being, my future, that it will be this way forever. It is a disorder that will probably stick with me forever, but I have found many ways to cope and I am grateful to have such massive support systems in my life.

I started getting better when I began to see a therapist. Talking it out to a professional helped and I wish I had gone sooner. After every appointment, I wouldn’t dissociate for a few days.

Together, we came up with a few “grounding techniques”, in other words, exercises to keep your brain from going down dissociation road. Coping with a mental illness is different for everyone, but these few practices have helped me greatly along the way.

The first step was accepting the fact that I have a brain disorder. This is huge because dissociation can’t be pushed under the rug easily. Talk about it, write about it, embrace it. Accepting it leads to improvement.

It’s never a bad thing to have a good cry over it, but don’t bring on too much negative thinking. Being optimistic is the greatest grounding technique.

Don’t forget to take care of yourself, even though the simplest things seem to be very hard. Have something to eat, take a hot bath or shower, listen to music, laugh. Start meditating every morning.

Repeat positive mantras to yourself throughout the day. Talk to the people you love. Communicate with your partner. Go for a walk, just to get out of the house. As scary as some of these things seem, it’s scarier to let the dissociation control your life.

If you struggle with dissociation, you are not alone. No, you aren’t losing your mind. You aren’t actually living in a simulation and your life is not a dream.

Your feet are on the ground, your friends and loved ones are real life people, and inside you have a heart that is beating and capable of feeling emotion. Dissociation is a silent slayer, a common mental illness that should be discussed more and brought to light.

It’s an odd and at times frightening feeling that can really take a toll on your well-being without anyone else being aware, much like anxiety and depression. You may have a classmate who floats to class in the afternoon too, or a professor that is very careful of every word they say because their brain is “off” and they feel disconnected.

Take the reins when your brain wants to float away. You’re surrounded by people that support you and people that experience exactly what you do; don’t be afraid to seek help during these troubled times.

Editorial opinions or comments expressed in this online edition of Interrobang newspaper reflect the views of the writer and are not those of the Interrobang or the Fanshawe Student Union. The Interrobang is published weekly by the Fanshawe Student Union at 1001 Fanshawe College Blvd., P.O. Box 7005, London, Ontario, N5Y 5R6 and distributed through the Fanshawe College community. Letters to the editor are welcome. All letters are subject to editing and should be emailed. All letters must be accompanied by contact information. Letters can also be submitted online by clicking here.