Talking Cash: Grexit - Understanding Greece's debt crisis

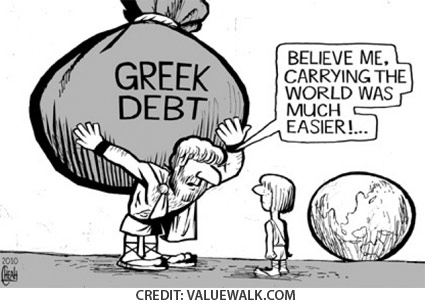

As the sinuous Greek debt situation continues to unfold on the world's financial stage, the increasing possibility of Greece exiting the European Union has created a new word to add to the financial lexicon: Grexit. The term was coined by Citigroup, an American bank, and is an amalgamation of the phrase "Greece Eurozone Exit." The word sounds vaguely dirty, but the whole situation of Greece's debt crisis is itself vaguely dirty, and in this week's column I'm going to try to explain at least a fraction of it as best I can.

I suppose financial analysts and journalists have gotten so weary of writing about the Greek debt tragedy that Grexit was created as a unanimous way of saving keystrokes. Perhaps the austerity measures imposed by the Greek government have become so tight they even apply to words describing Greece's financial problems, as if three words describing Greece exiting the Eurozone is simply more than what can be afforded.

So, what happens if Grexit occurs? What would cause Greece to Grexit out of the European Union, should that happen? It's complicated and I don't try to pretend to understand the entire situation. I would actually wager that so-called experts in the financial industry and in high-level public office don't necessarily understand the entire thing, let alone most of it. But I'll try to explain the basic problem and hope you don't make a Grexit yourself.

The euro was introduced to Greece in January 2001. Throughout the last couple of decades, Greece has been deficit spending, which means that they are spending more money each year than the country brings in. From 1999 to 2010, Greece's public debt percentage rose from 94 per cent to 142.8 per cent. Those numbers don't mean a whole lot by themselves, but the Eurozone's average debt percentage for 1999 was 71.7 per cent, which increased to 85.3 per cent in 2010. What these numbers indicate is that overall public debt has risen generally throughout the Eurozone, but this rise has been particularly dramatic in Greece.

In April 2010, Greek's debt rating was decreased to junk status by Standard & Poor's (S&P). S&P is a ratings agency that basically gives their opinion on the credit quality of a country or company. The highest rating S&P gives out is AAA. A country with a AAA credit rating is one that is highly unlikely to default on its debt. Some of you may recall that the United States had their credit rating downgraded last summer, and what a huge issue that was in financial markets.

This is kind of like a credit score for countries and companies. Junk status means that Greece's credit status is so low that their credit score is junk, literally. So, the possibility of Greece defaulting on their debt is quite highly relative to another country that grades AAA, as an example. S&P estimated that if Greece defaulted on its debt, investors could fail to get anywhere from 30 to 50 per cent of their money back.

Greece represents only 2.5 per cent of the Eurozone's economy. It's pretty small compared to the rest of Europe. The issue thus seems not so much to fear that if Greece were to leave the European Union (or remain in the EU but default on its debt) the entire union would collapse, but moreso to be a lack of confidence in the EU to manage its overall fiscal policy. In other words, it really scares investors that something terrible could also happen to Spain, Portugal, Italy or another one of the major indebted European countries and spread to the more stable Euro members, like Germany and France. If this happens, it's anyone's guess how bad things can get in Europe. One thing is for sure: there will certainly be no shortage of combinations of countries with the word 'exit.'

Jeremy Wall is studying Professional Financial Services at Fanshawe College. He holds an Honours Bachelor of Arts from the University of Western Ontario.