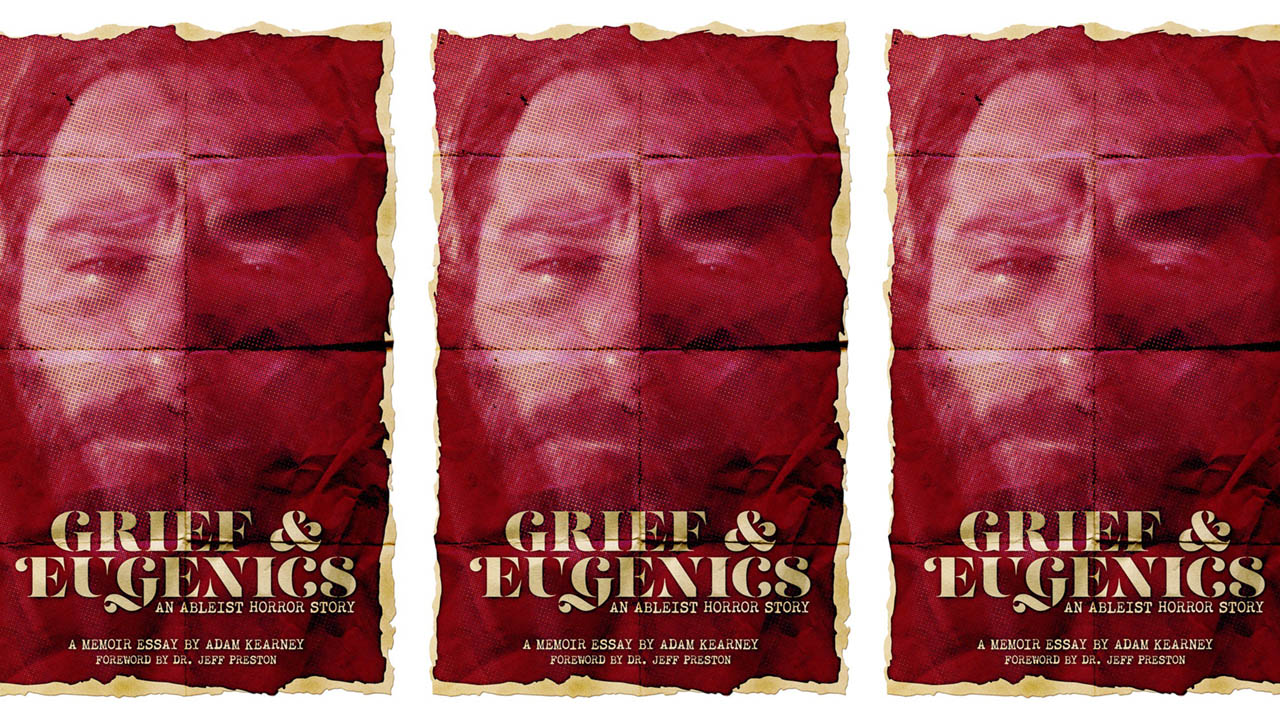

Grief & Eugenics: An Ableist Horror Story, Part Ten

CREDIT: ADAM D. KEARNEY

CREDIT: ADAM D. KEARNEYThis installment chronicles Adam’s life in the years after his separation from Jolene.

This article is Part Ten in a series of excerpts from Fanshawe grad Adam D. Kearney’s essay, Grief & Eugenics: An Ableist Horror Story.

Before things got bad with the separation and while we were still going to couples therapy, we had started to attend a grief group specifically for infant and pregnancy loss. It was put on by the local group Bereaved Families of Ontario-Southwest Region. There were two other couples and a couple of folks who came on their own, all of whom coming from different situations. Some just weeks out from their loss, some were years out. However, we all came together because of our shared tragic experience.

Unfortunately I was rather lost in things breaking down with Jolene and I found myself distracted at times by that. She had asked that I not bring it up during these group sessions and I respected that until the last one. When it was my time to share I broke down bawling (which is not out of the norm for groups like these) and explained that I was grieving the losses of our children while also trying to grieve the loss of our relationship. When the session was done I just got up and left, without getting anyone’s number or contact information. Shortly after losing Jonas a counselor had recommended the “Grief Recovery Handbook” to me, which I had at home, so naturally I thought I was good. What transpired over the next couple of years was not pretty.

WAKE UP

How the fuck did I get to this point? I was a hot mess. Whenever anyone asked how I was doing my answer was always “I am doing ok,” but we both knew that was a lie. It took me getting sober in 2020 to really start to piece a lot of this story together. Slowly connecting the dots, making the connections I hadn’t been able to see before.

My relationship with alcohol was never a healthy one. My family has always enjoyed sharing countless beverages when we came together and so it was always around. There had been a few family members who had struggled with their drinking but I only found that out much later. The biggest eureka moment came when I put a few key moments in my life together, and realized how they lined up to set me on the path that led me here.

First was the shift from being a camper to becoming a counselor. Yes, it allowed me a lot of independence and the ability to be of service to an organization that had given me a lot during my youth. This transition however removed me from my peer group who helped me add context and understanding to life with disability. Sure, I was still in their company, but being staff at camp led me to make stronger bonds with non disabled folks and, at times, made me feel like I needed to prove why I was different from the campers. There was a lot of negativity surrounding my identity with disability and, more specifically, a lot of grief. Not only grief brought on by friends losing their lives due to complications brought on by disability, but the grief of being excluded from aspects of social life because of my disability. This fractured the perception of who I was and pushed me to disassociate from the community and my identity. If my new non disabled peer group could see me as “less disabled” then I was able to move further away from having to deal with this grief.

Second, with Osteogenesis Imperfecta something strange happens as you reach adolescence — your rates of fracturing drop off as you stop growing. Not only was I not breaking bones all the time, but I was also not having to get my rods replaced which meant no more surgeries. What transpired was a 20 year stretch without any major breaks or surgeries, allowing me to live a social life without any major disability flare ups.

Third, booze. With trying to be seen as less disabled came a tremendous amount of social anxiety. Drinking turned out to help out in a couple of different ways. It helped me feel like I was blending in when I would go drinking with my friends. Being 4’2” and going drink for drink with my friends who were much bigger than me never ended well. Puking, blacking out, and passing out were a common occurrence. Not only did drinking act as a way to fit in, but it also took the edge off of the social anxiety of trying to do so as well. This would come around to get me in the end.

During my drinking days I adopted a lot of ableist views and I started to gather a tremendous amount of internalized ableism. I really would try to distance myself from other people with disabilities in hopes of not having to deal with my own. By the time Jolene came into my life I didn't see any value in a life with disability and because I compartmentalized my identity, I hated the part of me that I saw as being disabled. This was where I was coming from when I was making decisions about the viability of embryos. By the time I started to realize the gravity of my situation I didn’t have anyone around me to talk to about it. So I turned to a bottle. I didn’t want to live but at the same time I was far too afraid of dying.

In the end I drank to numb all of these feelings. I drank so much that when I didn’t have alcohol in my system the anxiety and depression crashed over me in a horribly overwhelming way. I still remember days where I would pour myself a shot of whiskey because the thought of drying out was just too scary. I would cry while I filled a shot glass, not wanting to continue drinking, but also not wanting to feel what I felt. I knew I had a problem. I would try quitting multiple times, but it would never stick. I would get a week in and convince myself I had it under control then just find myself back in the same situation. Luckily enough I had a couple of close friends who would talk to me about their sobriety and their experiences with the secret society known as Alcoholics Anonymous. Being active in AA has helped me stay stopped.

The biggest problem I found once I got sober and didn’t have my crutch alcohol any more was that I had to find ways to actually work on my problems. I had hoped for too long that time would just magically heal all my wounds and solve all my problems. Turns out nothing happens if you don’t put the work into it yourself. The rooms of AA were a big help — I found a particular secular group (none of the God/Higher Power talk) I still go to today and chair the Tuesday night meeting for. If you are looking for a meeting, get in touch with me and I will give you the details. One thing that folks say a lot in that meeting is “the opposite of addiction is connection.” I slowly began to understand how talking to another person with a shared life experience can provide insight and context to your own thoughts, feelings and emotions.

To be continued…

This memoir essay was published as a zine in Jan. 2023. If you enjoy it and feel you would like to support the author, you can find a pay what you can PDF or purchase a physical copy at handcutcompany.com.

Editorial opinions or comments expressed in this online edition of Interrobang newspaper reflect the views of the writer and are not those of the Interrobang or the Fanshawe Student Union. The Interrobang is published weekly by the Fanshawe Student Union at 1001 Fanshawe College Blvd., P.O. Box 7005, London, Ontario, N5Y 5R6 and distributed through the Fanshawe College community. Letters to the editor are welcome. All letters are subject to editing and should be emailed. All letters must be accompanied by contact information. Letters can also be submitted online by clicking here.