Educational inequalities impact Aboriginal students

CREDIT: KERRA SEAY

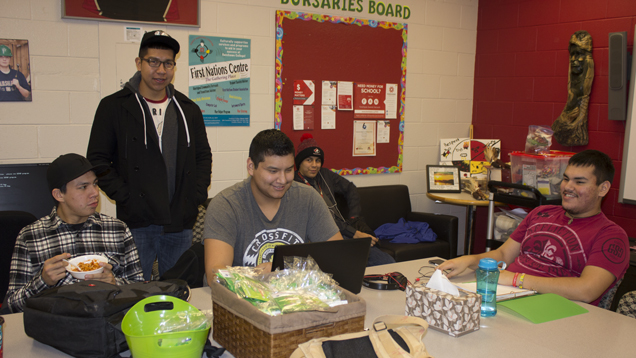

CREDIT: KERRA SEAYThe First Nations centre on campus offers support to Aboriginal students studying at Fanshawe.

After graduation, many young students are faced with a decision of whether to go on to post-secondary education. However, that may not be the case for everyone.

In 2011, Open Canada found that 78 per cent of non-Indigenous Canadians will graduate and pursue a post-secondary education, while members of a First Nations community will likely only have 35 per cent of their youth continuing on with school. This gap has now become alarmingly large and the time has come for something to be done to close this gap.

So how does this gap start? For many, the gap begins to form at a young age during the early stages of education. A teacher in British Columbia told the Toronto Star that, “It is hard to learn if you are cold, hungry and worried.”

Students that come from a low-income family have many concerns on their mind other than school, like basic needs. To ask these children to focus on learning instead of their hunger may be quite a difficult task. This creates a slippery slope of falling behind year after year.

In contrast, children from higher income families will often have an easier time focusing in class. On top of this, many of them have likely been exposed already to early childhood education such as pre-school, have access to tutoring services and more.

For children living on a First Nations reserve, their chances of living in poverty increase. The Center for Social Justice found that in 2003, 52 per cent of all aboriginal children in Ontario were living in poverty. This means that many of the children on the reserve are at a disadvantage and will face more challenges when they begin their education. The challenges could range anywhere from being distracted by their lack of basic needs or parents not having the ability to help their children with schoolwork. The gap further widens when some children living in poverty are wrongfully deemed the ‘bad' children who have to attend a ‘bad' and underfunded school.

Moving forward to graduation of secondary school, many of the youth that have grown up in poverty and in a disadvantaged situation now have an even bigger struggle to defeat — tuition costs. Over the last 20 years, tuition costs have more than doubled across the nation. For many, the daunting costs are enough for them to choose heading straight into the workforce after graduating high school.

For those who want to continue their education, they often need to find a ways to cover these costs, through loans, scholarships and grants. Without proper guidance on how to apply for many of these services, youth may find the debt of school quickly piling up. This alone could be enough for students considering postsecondary education to decide not to go at all.

Daniel Kennedy is the Aboriginal community outreach and transitions advisor at Fanshawe. He grew up on a local reserve, Oneida Nation of the Thames, and has been able to help break down some of the barriers and stigmas for native students coming to Fanshawe. Kennedy spoke about intergenerational trauma, something that many native students struggle with.

Kennedy said, “Essentially it is when you are being affected by things that have happened to your family.” For some native students, their parents or grandparents may have had traumatizing experiences growing up in residential schools. These kinds of events can be passed down through generations without even realizing it.

“It takes a long time for a group of people to fix this intergenerational trauma,” Kennedy said.

For Fanshawe student and Western University graduate Chelsey Nicholas, she did not experience these difficulties herself, but she has witnessed others who have. Nicholas grew up on the largest reserve in Canada, Six Nations.

Being raised by parents who have a background in education, her family knew the value of continuing on with postsecondary education. This push from her parents helped aid in her success through secondary school, which is a large determinant for getting accepted into postsecondary schools. For Nicholas, leaving the reserve to go to university and college was highly encouraged. However, Nicholas said her experience is an uncommon one.

“This is a rare case on the reserve. Most young people on the reserve don't grow up with the same support system that I had and it makes it much more difficult to continue their educations,” she said.

After graduating from Western, she took a break before deciding to come to Fanshawe for the Medical Radiation Technology program. At that point, trying to gain funding was more difficult because after graduating university she was listed as low priority. Like many other students, she was then forced to self-fund any way she could until funding became available again.

In terms of fixing the issue of native students accessing a proper education, starting out young is best. British Columbia has begun to offer lower costs of early childhood care so that children can start their education before entering kindergarten. In elementary school, there are efforts to try and keep the education quality across schools equal so that there are no longer schools that are deemed the ‘bad' schools.

In Manitoba and Ontario, the worldwide program Right to Play has been implemented to engage native youth in extracurricular activities where they will also have a chance to learn valuable life skills. In addition to this, across Canada, Me to We has created two distinct and impactful Aboriginal leadership programs, Sacred Circle and Spirit of Canada, that are both designed to help build leadership skills as well as educate youth on their native culture.

In addition, educational advocates have begun connecting with the youth living on reserves. This kind of program is designed to help inform all generations on ways to tackle tuition costs as well as the values of continuing education.

At Fanshawe there is a program specifically targeted to Aboriginal students. Kennedy explained that Fanshawe offers a General Arts and Science diploma in First Nations studies.

“It's an articulation agreement with Western University. Students that complete the two year diploma program are able to transfer a year's worth of credits to Western.” Kennedy mentioned how “this gives aboriginal students a good foot in the door when coming off the reserve and entering college and university.”

In addition to offering programs specific to the native community, Fanshawe has a First Nations center for aboriginal students. “It is a student service that is focused on student success. We really try to give the students a home away from home,” Kennedy said. Often there is a fear of culture shock or difficulty acclimating to a new society off the reserve. This service is there for students so that they can meet with other students and bond over similar experience in coming to college. Having these kinds of programs in place, like what Fanshawe provides, is a huge step in the direction of closing this education gap.