Different ways to ID species lead to schism within science community

CREDIT: SHYAMAL, WIKIPEDIA

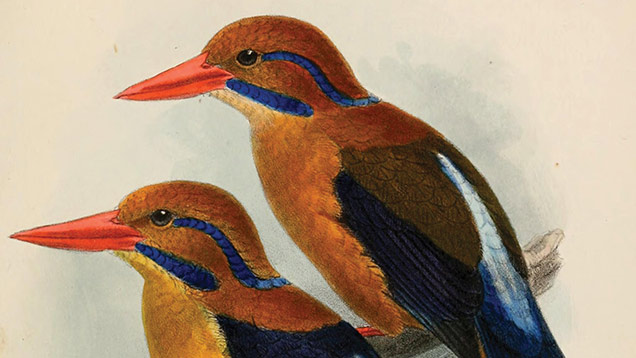

CREDIT: SHYAMAL, WIKIPEDIAThe rare moustached kingfisher was found, captured and killed for research purposes after 20 years of researchers looking for it. The killing of the bird sparked the question where do we draw the line?

Stretching east of Papua, New Guinea, the Solomon Islands are host to a variety of species. One that has specifically eluded ornithologists, those who study birds, is the moustached kingfisher.

The moustached kingfisher is brilliantly coloured blue and tawny brown; but only two have ever been found, both brought in dead by hunters to bird collectors in the ’20s, both female.

Now, after 20 years of stumbling through the Solomon Islands, researchers said they finally came across the ultimate specimen, a live male kingfisher in its natural habitat. The bird was caught for measurements and photographs, and then was killed so it could be preserved for further research.

The researchers said they estimated the total live count of the moustached kingfisher to be around 4000 with locals and sound recordings, and that while being rare to science, it was not a harm to the overall population to remove a single male.

The practice is common, and it’s how many people see taxidermy collections of rodents and fish, or dazzling displays of butterflies and beetles at museums, albeit many from differing times, caught by some who are now viewed to be profiteers and big game hunters.

Recently the practice has stirred up controversy within the scientific community.

On one side of the argument are researchers and field scientists who say collecting a specimen is the gold standard for identifying a new species. Their argument is that without it things like morphological changes, genomic data and non-calculable aspects, bringing wonder and joy to museum goers would be impossible.

The other side of the argument counters that the practice is out-dated and holds no place in a society trying to preserve species from extinction.

The scientific community remembers its previous follies such as with the Auk. The Auk was an Atlantic sea bird already suffering population decline; it was then hunted to extinction in the nineteenth century due to its resemblance to penguins, and from scientists driving up the cost of the bird due to their rarity, which led to more Auks being killed.

The whole fiasco was well documented and leaves a mark on field studies and specimen collecting to this day.

Dr. Cheryl Ketola, professor and co-ordinator for Fanshawe’s Biotechnology program, believes killing a rare animal, one possibly close to extinction, is morally wrong.

With a recent paper identifying a rare type of bee fly species by hi-res photos alone, Ketola said the technology was a start, but other available scientific tools are even better.

“Identifying [species] on hi-res alone can be risky if there’s really minute differences.”

According to Ketola, genomic technology is used to identify a potential new species more accurately. For example, researchers can take a sample of blood and test it against radioactively marked DNA sequences called probes; they can then use the results to look for similarities in the new species’ blood as well.

Ketola said using genetic probes is more of a “gold standard” in today’s science world.

“It’s really scary, when do you draw the line of when it’s appropriate and when it’s not ...when do you decide that the population is at risk?” Ketola said. She added that the decision to collect the entire bird, as opposed to gathering only skin, blood or feather samples for later genomic study was at the very least invasive on the researcher’s part.

“To capture the bird and then euthanize it, that’s disgusting, that’s awful.”

Who knows, maybe the way to solve this dilemma in the future is for scientists to collect a simple blood sample of the species in question, and then clone a specimen for every museum or school that needed one for their research or exhibits.

As the worldwide White Rhino population fell to five individuals this year, and thousands of species in both the Animalia and Plantae kingdoms are continually threatened by deforestation for agricultural and residential purposes every day, some decisive thinking will be needed over the next decade.

Scientists will have to ask themselves which choice is more appealing, or appalling, to public perception: growing clones that are bound to end up dead for scientific purposes or taking specimens from a natural habitat in which the species may actually be the last of it’s kind.