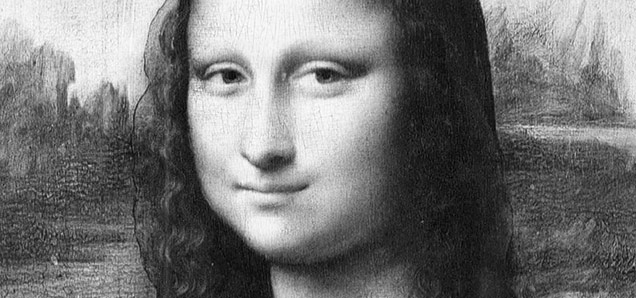

ARTiculation: Mona Lisa smile

For centuries, the Mona Lisa has attracted a staggering amount of attention. It may be the most recognizable art piece today, up in the ranks along with the Sistine Chapel paintings, Michaelangelo's David and Monet's Water Lilies. I remember when I was younger and first introduced to her, I wasn't sure why the painting was so famous, and reasoned that it was likely because she has no eyebrows. And now, after years of studying art and delving into theory, I still find myself staring at her and wondering. To some, looking at her sends you back to da Vinci's studio, watching him lightly and calculatedly stroke the canvas with a soft brush. But a major part of it is because she's so entrancing, sitting there and smirking at you with a nagging, immortalized taunt.

In an era when the subjects in art were (for the vast majority) religious figures or royalty, the Mona Lisa gained some attention because she wasn't anybody in the public eye. And by the mid-19th century, poets looked to her as an attainable beauty, and put her in the starring role of their fantasies. She quickly rose to fame as an “everyday girl” beauty. After she gained prominence, people began to wonder who she was. The question has been begged for years, and people have devoted their lives to deciphering the identity of the Mona Lisa.

Everyone, meet Lisa del Giocondo. Also known as Mona Lisa.

Lisa was born in 1479 in Florence to a middle class couple. Her father had survived two wives who both died while giving birth to Lisa's siblings. They were a farm family, harvesting wheat and making wine. She had a normal childhood, and married a man named Franceso when she was 15, obtaining the last name del Giocondo (which is where the Italian name for the painting “La Gioconda” is from).

Her husband commissioned da Vinci to paint a portrait of Lisa because she had “a noble spirit and as a faithful wife.” She had five children, one of whom died when she was very young. They also grew up comfortable and in a middle class environment. Two of her daughters became nuns. Francesco is rumoured to have died in the plague, so when Lisa was growing older and didn't have a husband to care for her, they took her to stay at a convent where she lived until she died.

Now that you know her, does it make you feel more connected to the painting? Will looking into her eyes the next time you see her remember that she was a person, not just a figment of the pigment? Today, context means too much in art. When the Mona Lisa was painted (and up until the mid-1800s) artists were very focused on the technique of the painting rather than the subject matter. But in modern art, context is so important to the meaning of a piece.

Famous artist Ai Wei Wei created a piece where a gallery wall was covered entirely in pieces of standard printer paper with names typed on it. They were fashioned together so it was just a huge, long list of nearly 5,000 names.

When his show came to the AGO in Toronto, I went with a friend to see it. We came to that piece, and my friend glanced at it and moved on, but I stood there haunted. Without the context of the piece, they were just Chinese characters on pieces of paper. But I knew that they were names of the children who lost their lives in the massive earthquake in China.

When the earthquake happened, the Chinese government refused to search for and acknowledge the children who were killed. So Wei Wei spent a long time talking to people, going through records and compiling this list to honour the young lives that were taken at the expense of their government. It was chilling to stand there and recognize both the individuals who lost their lives as well as Ai Wei Wei's dedication to the people of his country. Modern art gives much more weight to the subject matter than art of the past, and unless we understand what's going on in our world, it won't make much sense.

The Mona Lisa is a painting of another girl that lived in another era in another country. It's so easy to remove yourself from her. But art can be appreciated so much more if you understand where it came from, what purpose it served. There are so many stories nested into art of the past. And there are so many stories being painted right now, you just have to look between the brush strokes.

Editorial opinions or comments expressed in this online edition of Interrobang newspaper reflect the views of the writer and are not those of the Interrobang or the Fanshawe Student Union. The Interrobang is published weekly by the Fanshawe Student Union at 1001 Fanshawe College Blvd., P.O. Box 7005, London, Ontario, N5Y 5R6 and distributed through the Fanshawe College community. Letters to the editor are welcome. All letters are subject to editing and should be emailed. All letters must be accompanied by contact information. Letters can also be submitted online by clicking here.