Notes From Day Seven: 9/11 and a lesson from St. Paul's

I was 11 years old when my father took me to New York in 1964. We drove during the winter, managing our way through a snowstorm. At one point a state trooper talked to Dad and I remember clearly the American accent, the first I ever heard coming from a live person. In the city itself, someone gave us a ride in their Buick Riviera. It felt decadent — sitting in the back of that car, hearing the bass-heavy rock 'n roll coming from the speaker mounted in the middle of the rear white leather seat. We planned to look at the tallest building in the world: the Empire State Building.

We went to a restaurant. I noticed a magazine article mounted on a wall. It showed an artist's rendering of two towers. I read enough of the article to understand that the towers were being planned and that they would be known as the World Trade Center.

Fast-forward 48 years. Visiting my brother in New York during the spring of 2002, I was looking down into the six hectares where the twin towers had been built — but were now gone. Down below it looked as if trucks were hauling out the last of the concrete and steel that had held up the towers.

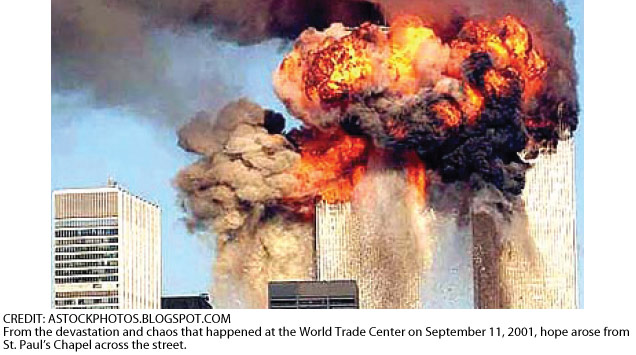

Maybe, like me this past week, you were motivated to look at some of the online videos of the plane exploding into the second tower. Others show people climbing over each other to get breathable air from windows, separated by 100 stories from the opportunity to reunite with their families and to continue living. It's not pleasant viewing.

The Reverend Lyndon Harris of St. Paul's Chapel, a church across the street from the towers, wrote about walking to the church building the morning after. In an online article he said he expected to find the church destroyed. But coming near the site, he saw its spire still standing. Other than being covered by soot and ash, the building was unscathed. Rev. Harris wrote that "St. Paul's had been spared," not because any of its members were "any holier" than those who had died "across the street," but because they now "had a big job to do."

According to Harris, during the months that followed, St. Paul's became a centre for help and care. It began with providing drinks and food for the rescue workers. It involved clergy, theology students, podiatrists, soccer moms and people of all kinds. By the time it was over, more than 5,000 people, many from other parts of the U.S., had come to assist.

Harris wrote, "We just got up, day after day, dressed accordingly, and went about the monumental task of trying to make sense out of absurdity, bring order out of chaos and reclaim humanity from the violence that sought to make human life less human."

Why do "bad things happen to good people?" Why do terror attacks happen to office workers trying to go about their ordinary business?

Maybe an even tougher question is: how should we respond when people around us are in real trouble? The people of St. Paul's got it right. A cup of cold water. Space to rest. Prayer. Soup and sandwiches. Bandages and medicine. "Reclaiming humanity." Caring for people where others have done their worst.

We don't have to wait for a terror attack or other catastrophe to do as the folks of St. Paul's did. Before today is over, all of us will have the chance to help someone with a supportive word or a random act of kindness. Hopefully, we'll make the best of those opportunities.

Editorial opinions or comments expressed in this online edition of Interrobang newspaper reflect the views of the writer and are not those of the Interrobang or the Fanshawe Student Union. The Interrobang is published weekly by the Fanshawe Student Union at 1001 Fanshawe College Blvd., P.O. Box 7005, London, Ontario, N5Y 5R6 and distributed through the Fanshawe College community. Letters to the editor are welcome. All letters are subject to editing and should be emailed. All letters must be accompanied by contact information. Letters can also be submitted online by clicking here.