ARTiculation: Chuck Close close up

CREDIT: WHITECUBE.COM

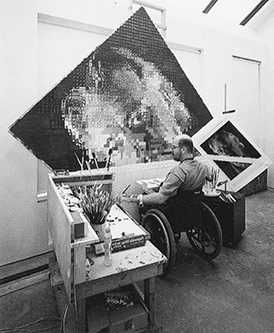

CREDIT: WHITECUBE.COMArtist Chuck Close paints in a studio that has been modified to accommodate his range of motion.

“Inspiration is for amateurs. The rest of us just show up and get to work.” — Chuck Close

I stood in the art gallery like a child studying an ant crawling up the wall: hands clasped behind my back, butt sticking out so I don't touch anything, neck craned forward, and my nose two inches away from the canvas. I searched the painting for any evidence of a brushstroke. It was smooth. The square foot of blended flesh tones didn't seem like much of anything from that close, but as I took steps backward, keeping my eye on the gigantic, wall-sized portrait, I began to see that I was, in fact, nose-to-nose with a man. A few more steps backward, then all the way to the opposite side of the room, and I was now having a staring contest with the exquisitely focused man on the canvas. I felt connected to him— like he was my father giving me a stern lecture. The unrelenting stare caused me to look away, uncomfortable with the intimacy. As I broke eye contact and squeezed my eyes shut, it became clear that I was being taught a lesson, not by my own father, but by the father of modern photo realism, Chuck Close.

It was Georgia O'Keeffe, famed for painting large-scale flowers, who said, “I paint them because they're cheaper than models and they don't move.” Although her statement was less literal in nature, there are many artists who've birthed a body of work not out of careful selection, but out of circumstance.

Already a prominent artist in the modern art scene, Chuck Close was in his late 40's when he suffered an injury that left him paralyzed from the neck down. When faced with the question of what he would do with his life from that point forward, he briefly considered conjuring concepts for paintings and having them executed by assistants like Warhol had done. But in his earlier years, when he was attending Yale for fine art, sculptor Richard Serra influenced Close to believe that the creative process — that is, for Close, putting brush to canvas — is what gives the artist their exclusive style. Without the process of painting, he thought, he wouldn't be satisfied with his body of work. Unable to cope with the fact that he may never pick up a brush again, he underwent rigorous physiotherapy in order to regain some range of motion in his arms. And with time and tenacity, that is what he did.

Chuck Close's process has changed. He takes up to a decade to finish a group of portraits. Rather than moving around the canvas to paint his portraits, he has in place installed a system akin to pulleys that allows the canvas to rotate to whatever angle he requires, and has a slit cut into the floor so that the canvas can slide up and down according to where he's working on the plane. He paints with the brush taped to his arm.

Excuses, if you let them, can grab hold of us like a fast-spreading virus. It isn't long before you're paralyzed with fear of something: perceived lack of talent, inspiration, money, physicality. But it's those like Chuck Close who work ferociously within their circumstance and process that end up with incredible results.

As I opened my eyes and raised them to match the stare of the man on the canvas once more, a desire stronger than my petulance bubbled within me. It is the ability to hold onto that intention that defines if one truly is determined. Chuck Close thinks that inspiration is for amateurs, but amateurs is what we are if we haven't been inspired by his moxie.

Editorial opinions or comments expressed in this online edition of Interrobang newspaper reflect the views of the writer and are not those of the Interrobang or the Fanshawe Student Union. The Interrobang is published weekly by the Fanshawe Student Union at 1001 Fanshawe College Blvd., P.O. Box 7005, London, Ontario, N5Y 5R6 and distributed through the Fanshawe College community. Letters to the editor are welcome. All letters are subject to editing and should be emailed. All letters must be accompanied by contact information. Letters can also be submitted online by clicking here.